No 5: ON FRAMING PARTS 1 AND 2

LUCIA AUERBACH

Parsons School of Design

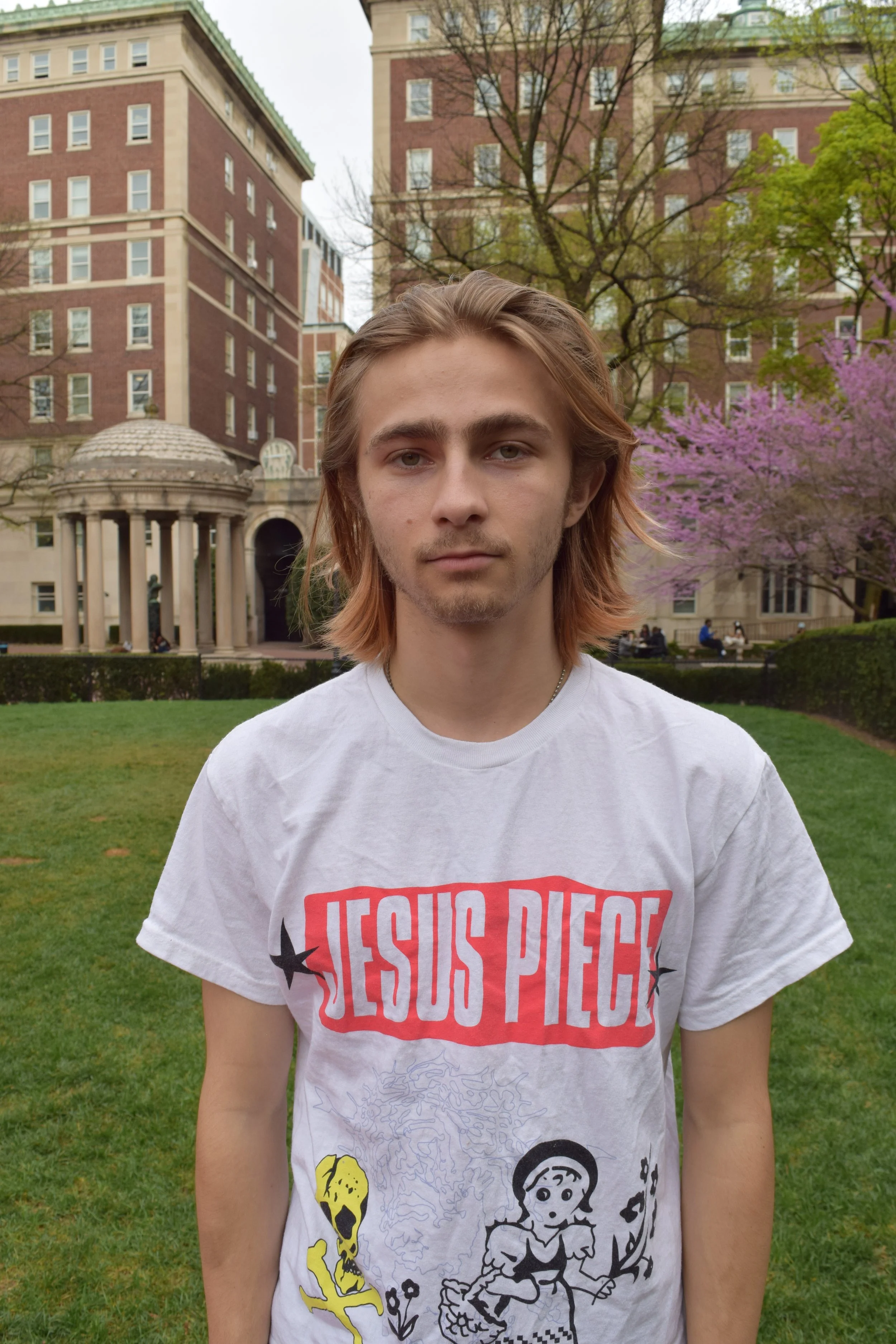

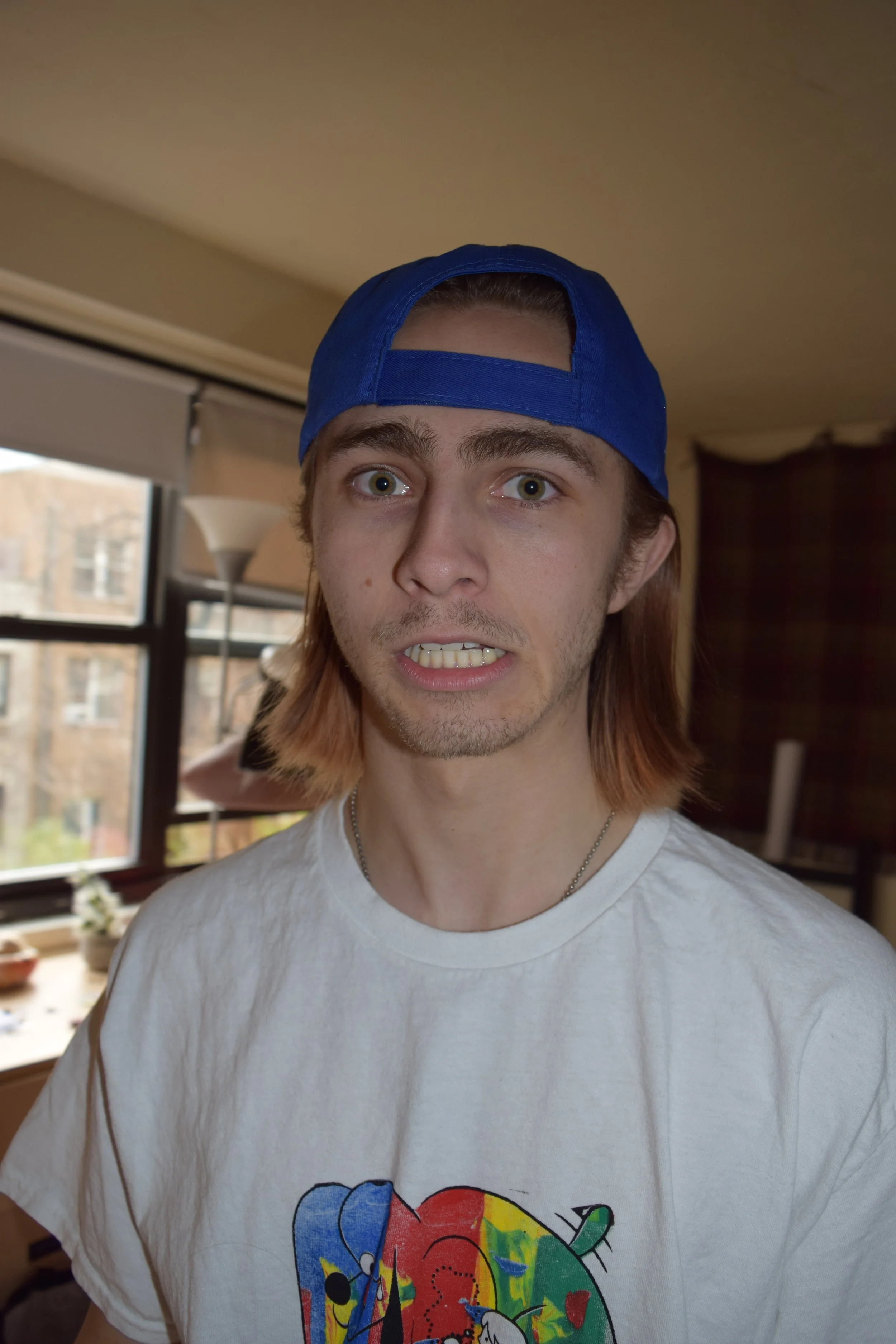

“Because I’m an asshole,” Charles Cutt said as he sat across from me on my dorm room bed. “If somebody came to me who is exactly the same as me, I would probably instinctively try to be different from him.”

∗ ∗ ∗

The morning after I had nearly broken my ankle, I hobbled down to East Fifth Avenue and 14th street to meet up with Charles and his newly found best friend, Leo Preston. They were an hour late. The pair brought me up to the large naturally lit dining hall. We ate warm sandwiches and fries while analyzing the framed photo that they had just purchased at the Chelsea flea market—the cause for their delay. The framed photo showed two men imprisoned, one enthusiastically looking up out the cell window while the other sat frustrated, yet stoic on the bunk-bed. Leo felt the duo resembled their own: flabbergasted and pensive but taking no real action about it.

We returned to their dorm room to prepare for a photoshoot for which they would both be modeling. The photographer did not arrive for at least another hour.

Leo gets a phone call from Julia Hirschman.

Julia Hirschman enters the dorm room.

We sit in Leo’s room as the two boys begin to back the framed jail portrait with cardboard. Julia hops onto Leo’s bed and lays down, propping her head up with her hand. She wears a pale pink babydoll slip dress, exposing her legs which are covered in self-imposed tattoos, psoriasis, and scars which I could not see. She also has a racoon hat on. The outfit did not make sense together, but the clashing personalities it displayed made sense for her character. I sat behind Charles on a spinning chair; looking over his grown out and orange dyed hair, I could see him struggle to cut the cardboard to fit into the frame. He ended up breaking the glass. They hung it up in the kitchen anyway.

The conversation veered to a story of an apartment he had recently visited. It’s owned by his friend’s father, a real artist.

“What makes you say that?” I asked.

“He paints. He’s an artist” Charles responded.

“No, I mean why do you say he’s a real artist?”

“He makes his money off of it.”

“So art is what? Monetary value?”

“No, not art. But being an artist.”

See they are two very distinctly separated things, art and artist. Art is what is expressed, whether it be in galleries or in the dark. Being an artist, however, is how you proceed to display and share and commodify that art. At least that’s a definition that made sense at the moment.

What artists choose to place on their easel, in their photography, on their clothing, in their electronic designs, in their frames: that is what we deem to be art. I refuse to believe that framed art—meaning the art object itself that is consumed by the artist or spectators—exhibits the authenticity that art demands. How can I trust that what is inside this piece of art is saying what I believe I am hearing? Is what is displayed in front of me, hung up in this frame, ever going to tell me the truth? How will I ever know if it is real art?

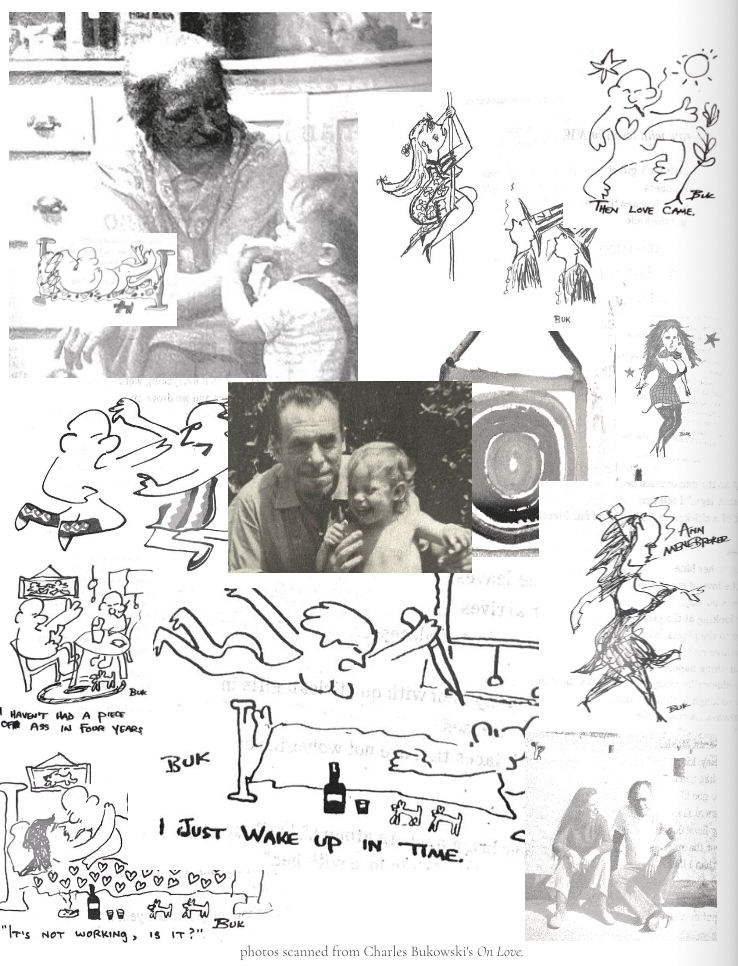

I will never know. Neither will you. Neither do young artists today. I see art as a form of disfiguring the self and past experiences. It loses a certain type of literal authenticity and instead creates what the artist wants to frame as their reality. We pick and choose what art means to us—but can this process of choosing be called art itself? Is it inherently a performance, like a Jackson Pollock painting, leaving bits of ash in his wake as his paint splatters begin to dance over a canvas sprawled on the floor? I’m sure his legs were covered in paint too. Is that art? But the photos of Pollock’s performance is my only understanding of his practice. It all exists within a frame. Even if I was there to see Pollock splatter himself, I am framing his emotional process through my own viewership.

Judith Butler acknowledges the frame’s nuanced nature in their chapter “Precarious Life, Grievable Life” in their book Frames of War: When is Life Grievable? published in 2009. They say that the verb “to be framed” evokes a complicated linguistic history, one that involves both penal systems and the art world. Inherently, when art is placed into its frame, it leaves out the greater context it came from. We lose sight of the social moment it is birthed from, what the artist was experiencing emotionally, or even the rest of the picture. Butler said:

When a picture is framed, any number of ways of commenting on or extending the picture may be at stake. But the frame tends to function, even in a minimalist form, as an editorial embellishment of the image, if not a self-commentation on the history of the frame itself. This sense that the frame implicitly guides the interpretation has some resonance with the idea of the frame as a false accusation (8, emphasis mine).

The frame becoming “an editorial embellishment of the image” asks my very same question: how does framing, or the portrayal of art, become a disfigurement of the art’s original form? I find it puzzling why Butler uses the word embellishment, however. Is the frame an addition instead of the detraction I’ve suspected?

Charles Cutt

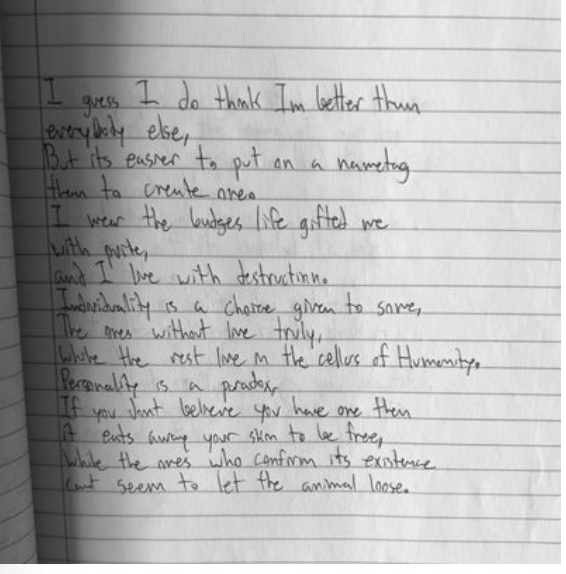

The last entry in Charles Cutt’s current poetry notebook was entitled Operation Ketamine. I read it when he wasn’t looking. It was a dizzying account of how the drug entered his system, focusing mostly on the somatic: the painful post-nasal drip that occurred after his inhalation, the intense thirst.

“How much of what you write is real?” I asked.

Charles is principally a fashion designer. The lack of financial backing for poetry swayed Charles to follow a route of marketable fashion instead. He does not consider his clothing to be poetry; they are two separate entities. His poetry airs on the side of “gross,” taking inspiration from the poet Charles Bukowski. He doesn’t mind how his fashion will inevitably take form—for now it is morphing into a form of environmental protest and commentary on punk ideology. But, he wouldn’t mind working for Abercrombie one day.

∗ ∗ ∗

For Charles, poetry is the unsaid. We first bonded three years ago over Bukowksi’s poetry. His thematics never really fell into what Charles believes to be the standard conventions of poetry; the poetry possesses a quality of beauty that prides itself on the grotesque.

“If most people who read my poetry also know about Bukowski, they would see I’m just a Bukowski rip-off” he said “but I also think, towards the end of my time at aftercare, I did a lot more personal style.”

He reads me the following unnamed poem:

This animal is an unfiltered, egotistical personality. He doesn’t claim it to be his own animal, rather one belonging to a distant other—one that exists off of misplaced pride. You can hear Bukowski handing Charles the pen in the first line when he utilizes his characteristic impudence and arrogance. Charles’ musing about Bukowski is not accidental, for Bukowski represents an exploration of the everlasting youth of a self in a way that other poets rarely dare to attempt: he lingered in his degeneracy and refused to age out of it. In Andrew J. Madigan’s “What Fame Is: Bukowski's Exploration of Self,” he asserts that Bukowski’s career was protected by his youth: “He has a young boy writing for him, nourished on raw meat and whiskey. The caged boy writes and protects Bukowski from forgetting the starving young poet in Barfly, from rejecting the past and the struggle, from becoming a self that a first self created” (16). I see that young Bukowski as what Charles’ poetry is clawing to become. Charles relishes in the notions of the ghastly: taboo sex and drug usage, overt egoism, the abandoned son. He does not hide from discussing what society has declared as appropriate romantic conventions. But he is actively choosing to not include these remarks in the art he displays—these ruminations are mainly contained in his various notebooks. His zeal for non-conformity in the ghastly poetic sense is left out of the frame in his fashion. The artistry captured in his fashion visually excludes the degeneracy that propelled him to pursue fashion in the first place. Instead, he alludes to the subversive in other forms, abandoning his Bukowski roots. He makes jackets with hidden spray can pockets so artists can continue to produce street art, or vandalism. He makes pants named after pansies, the derogatory term used to describe unmasculine and queer men. The audience consuming, viewing, wearing his work does not get to see his embrace of Bukowski’s poetry, but the fashion that follows it cannot be separated from his initial subversive inspirations.

Charles’ believes that poetry is the unsaid. Maybe this is because his remains unseen. He continues to leave it out of the frame.

“power corrupts,

life aborts

and all you have left

is a

bunch of

warts” (Bukowski 180).